december FEATURED artist |

Morning Mystique

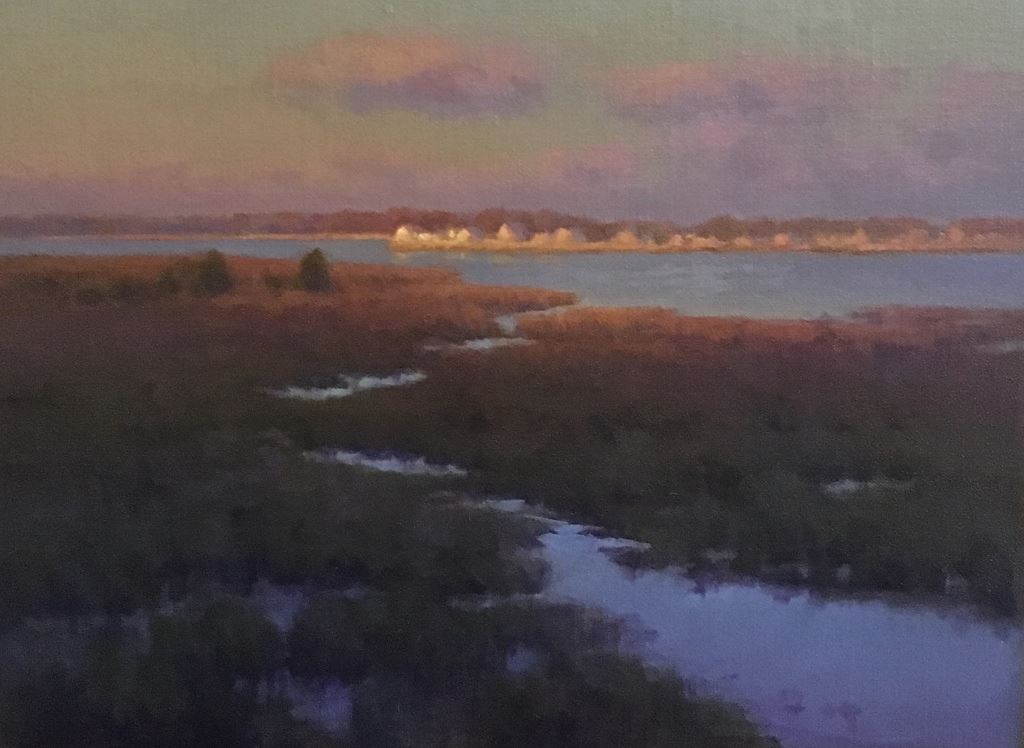

Pink Cloud Twilight

The Golden Hour

Plein Air

| From Children’s Book Illustrator to Landscape Artist: A Journey by Hillary Scott Like many creators of fine art, I started my career as a children’s book illustrator. In 2014 I switched from illustration to landscape painting and everything from my mindset to my creative approach changed, which has led to a complete reinvention of my work. I spent years copying photographs, creating work from my imagination and painting what I knew and not what I saw. Fortunately, this was acceptable for the style of work expected of me as a children’s book illustrator. However, the minute I decided to venture out of this space and into the world of realist landscape painter, I had a big problem. When I tried to cross over into the world of “fine art” with a skillset that had served me for 15 years as an illustrator, I was rejected from juried shows, had almost no sales and experienced a whole lot of frustration about why I couldn’t seem to paint the way those other artists could. I wanted nothing more than the ability to convey the magic I witnessed in my everyday travels. My taste was impeccable, but my skills sub par. Learning to see is undoubtably the most important skill any representational artist will learn and it starts with taking the time to observe what is in front of you, whether it is a figure, object or, in my case, nature. I fought this for years; it was easier to sit in front of my computer screen and paint from photographs with my own preconceived notions of how bright a sunset really is, or what the shadow colors are in a misty landscape versus a bright sunny day (spoiler alert: in my mind, they were exactly the same). I painted every blade of grass, every flower, and every single leaf with razor sharp edges because that was how they physically existed. That approach failed because it is not how the human eye sees the world. My workshop instructors all said, “Paint from life!” I had never done that and, quite frankly, it was overwhelming. It was hugely inconvenient to pack up all my paints, brushes, solvent, etc. and haul it outdoors where the weather could be unpredictable. Nothing stayed still and the light was constantly changing. However, I made myself do it and I have never regretted that decision. The more I painted from life, the better my work became. The easier my life in the studio also became, and this shift was huge. Even when I couldn’t get out to plein air paint, I had a much better understanding of what was really going on outside in various light situations and different times of day. When I didn’t have the ability to actually set up an easel and plein air paint, I actively observed--observed when I was driving my kids to school and games, observed when sitting outside in the backyard, observed when I went out to take photos. In effect, I wasn’t just taking photos; I was actually observing colors, values, and temperature shifts. Photos lie and blindly copying them was doing a major disservice to my work. Not only did I start training myself to see what was directly in front of me, I realized I had a complete lack of color understanding. I was accustomed to throwing color around freely, the brighter the better! I needed to learn to execute what I was seeing. This is where color charts came in. They are about as much fun as they sound, but surprisingly I found myself getting excited about the mixing of various colors. The time invested in learning to mix these colors paid off when I was plein air painting or painting in the studio. I could now execute what I was observing and, over time, my work started coming together. I have since made other adjustments through my artistic evolution; for example, I now consider myself more a poet and less a reporter of detail. I used to meticulously draw out my paintings on the canvas with every detail was accounted for. I mistakenly believed my ability to record every minute detail was the recipe for a great painting, but exactly the opposite was true. Less is more and what I choose to convey to my viewer is 100 percent my decision. My focus is now on large shapes and how they relate to one another, on mood, on light, on where my edges should be soft versus hard. Where can my painting use a hit of one of those gorgeous yet chromatic colors I once overused? I am now learning the delicate balance of painting what I see while utilizing my creative license, knowing where and when to push an element in my work—and when not to. This might be the hardest job of all. Push too hard and the work resembles something from the fantasy genre, but we artists must learn where to edit and what to omit, or we are simply recording information. That is not what an artist is. We all have our own unique take on the world and our job is to figure out how best to express that. To come full circle, the most valuable thing I’ve learned from my illustration experience is that a bit of imagination and creative license can transform what might be a very ordinary painting into something extraordinary. The difference now is that I have learned how to paint nature as it is, and once I learned that I was able to allow myself to break the rules where I see fit. In my opinion, a great landscape painting includes a little bit of mystery and a touch of magic while it stays true to the place it was inspired by--and the last element is only possible when one learns how to see. |